Yes, the Baron de Bérenger did exist.

A few years ago, while in London, I had the privilege of visiting the Kensington Central Library and exploring its archives under the guidance of Dave Walker, Local Studies Librarian. It was Dave who introduced me to the Baron de Bérenger, via the baron’s gun. Until then, I’d never heard of the man, but upon learning he had a flamboyant character, with a shade of fraud around the fringes, I became deeply interested. No, let us say, obsessively interested, and you do need to be obsessive about him, because he’s deuced elusive. Biographies do not abound. What we get are what Wikipedia calls stubs.

However, I quickly found a remarkable book he wrote, Helps and Hints How to Protect Life and Property with Instructions in Rifle and Pistol Shooting, &c. by Lt. Col. Baron de Bérenger.

The last part of the book is a description of his new Stadium, which, basically, is a venue for putting the author’s philosophy into action:

“Since it was to their national games that the Greeks and Romans owed alike superiority in muscular exertion and skill, and that mental loftiness, that noble daring, which changing, out of the arena, to patriotic self-devotion, furnished so many glorious examples,—it is obvious that the means thus employed by them claim our serious consideration, and are worthy of our adoption. Even, however, in our own times, it is to the fascinations of the field sports, and the arduous exertions of military duty, that we may ascribe an extraordinary development of our powers,—a great improvement of the symmetry and agility of the manly frame, and increased ability to endure exposure and fatigue.”

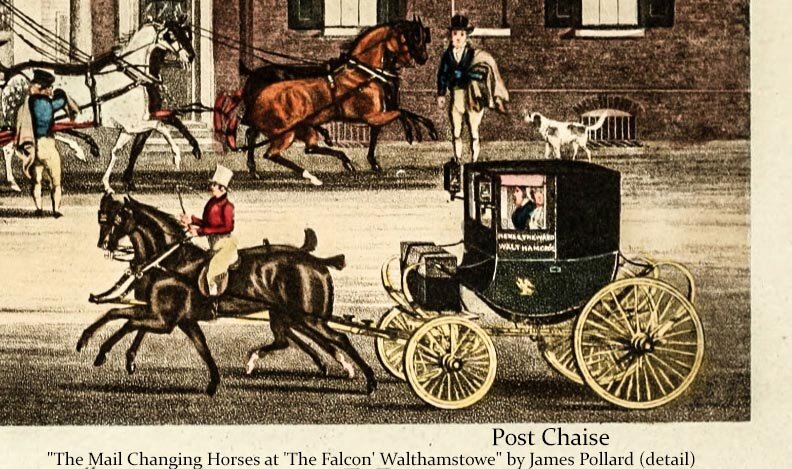

In 1830, de Bérenger bought Chelsea Farm, where he created “a spacious arena, and also distinct plots of ground, (the whole tastefully and expensively decorated, and provided with necessary implements, &c.) are purposely devoted to exercises, games, and pastimes, which, whilst under scientific instruction they ensure the acquirement of skilful activity and presence of mind, at the same time most powerfully tend in youthful practitioners to develope, and in those advanced in years to invigorate, the muscular powers, and undeniably to promote health in both, by stimulating digestion, causing serene repose, and averting numberless maladies resulting from irregularity in the secretions and other functions; for all of these, energetic exercises, relaxation from study, and cheerful pursuits, can alone preserve or best restore.” [The spelling is de Bérenger’s.]

George Cruikshank, Artificial Pigeon Shooting, at the Stadium, Chelsea ca 1834 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Bequest of Mrs. Eliza Cruikshank

This is the Stadium where Cassandra demonstrates the art of nearly killing a fellow with an umbrella. As adept as he was, the baron saw only limited use for an umbrella in self-defense. However, there was abundant material elsewhere on this topic. Though my sources came from much later in the century, it was easy enough to imagine someone as clever and determined as Cassandra Pomfret developing her own methods.

The Stadium became a pleasure garden, Cremorne Gardens, which is mainly where one encounters brief mentions of de Bérenger. But that developed at a later time than my historical setting, and is another, far less elusive subject altogether.

The Bartitsu Society offers a compact bio of de Bérenger.

There’s a short video on YouTube.

Here’s his petition, in relation to the fraud with which he was charged. I have to say, I love his writing. His personality comes through so vividly!