I happened to find myself in London, looking up at a statue of Florence Nightingale on her birthday. At the time, I was on a tour of Ben Franklin’s life in London, of all things. But the Florence Nightingale Museum was on my list of Places to Visit, and two days later, I ventured into the precincts of St. Thomas’s Hospital and thence to the museum.

Like so many of my generation, I first heard of Florence Nightingale in elementary school. It took a few decades for me to realize her significance. Even so, the museum was an eye opener. You can read the Wikipedia article for a detailed account of her life and accomplishments. For now, I’ll simply share some of the museum experience.

Please be aware that I do not have my laptop, but am working with tablet and phone, neither of which is ideal for a blog post, it turns out, which means you may expect workarounds, and maybe not so many links as usual. But since everybody doesn’t get to spend a month in London and be all nerdy history all the time, I hope you’ll enjoy traveling with me, despite the glitches.

Below is a gallery of images from the museum. A couple of notes:

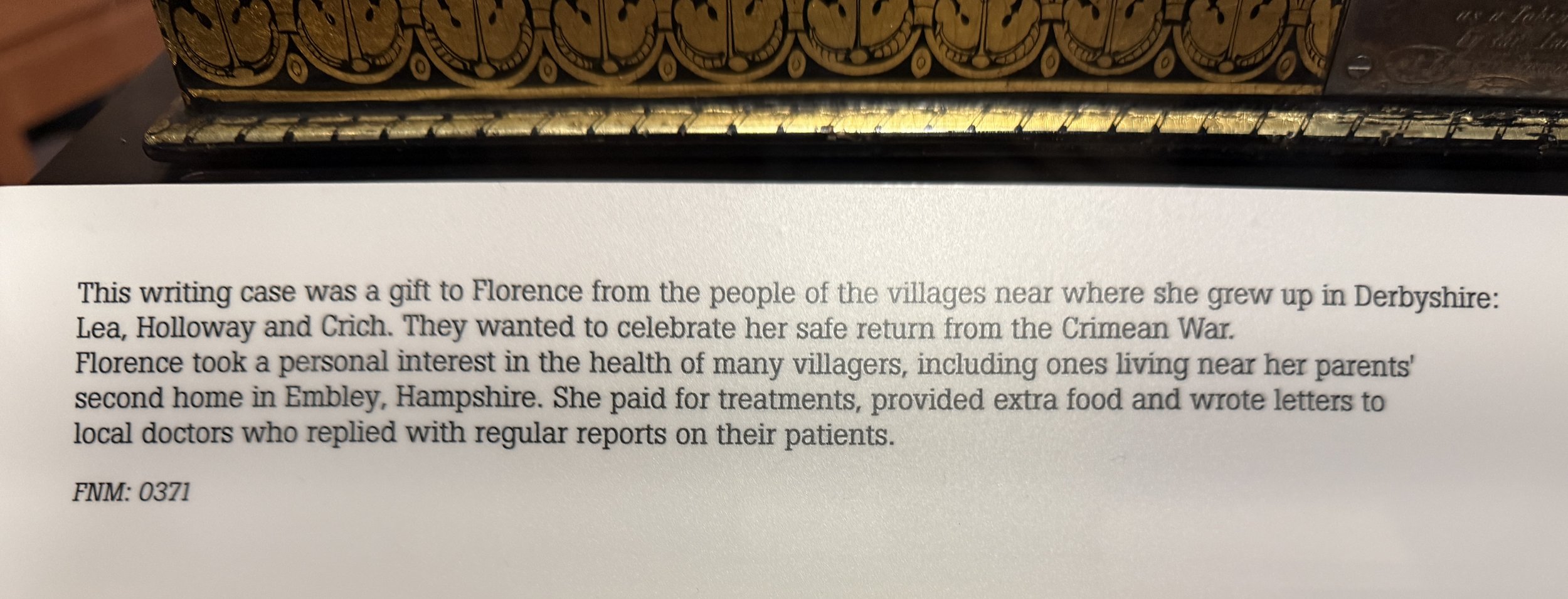

The photograph of Florence Nightingale was taken shortly after her return from the Crimea. She was ill, and had lost so much weight that her parents were horrified. She cut her hair while in the Crimea because it needed too much care—energy she wanted to reserve for her patients…and for dealing with the bureaucracy and the doctors.

By the way, she was quite tall for her time—5’8”—and I hope my metric system readers will be kind enough to translate that into understandable measurements.

The bed is the one she died in. (I may be mistaken, and it may be a reproduction, but I failed to make a note at the time.) Beside it is a phonograph, which allows you to hear a recording of her voice. You can access this recording on the Wikipedia page. The little box at the front of the photo contains a soap with her favorite scent.

I had heard of the chef Alexis Soyer. I hadn’t realized he was also in the Crimea, and made his own major contribution to saving lives.

Many of the placards are posted against what appear to be bandages or hospital dressings, and there is a sound effect meant to indicate rats scurrying through.

The courage of the women who went out to nurse under these nightmarish conditions is beyond my imagining. As to the men: War is hell, as, tragically, we continue to be reminded every day.