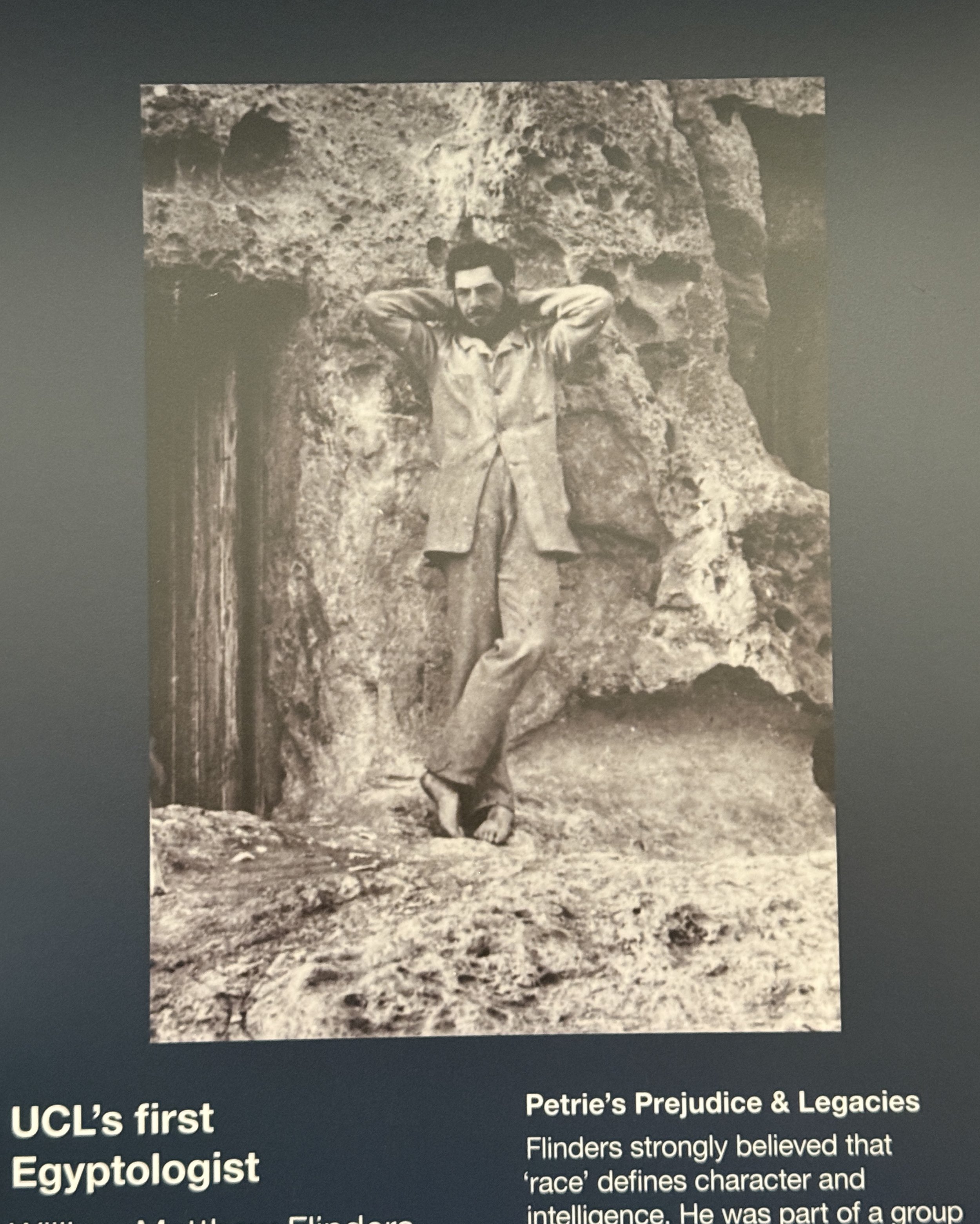

You’d think, given all the research I did for Mr. Impossible—not to mention my lifelong fascination with Egyptology—that I would have known all about the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaelogy. But I wrote that book quite a few years ago, when most of my research happened with books, and what was available online, while immensely helpful, wasn’t a fraction of what we find today.

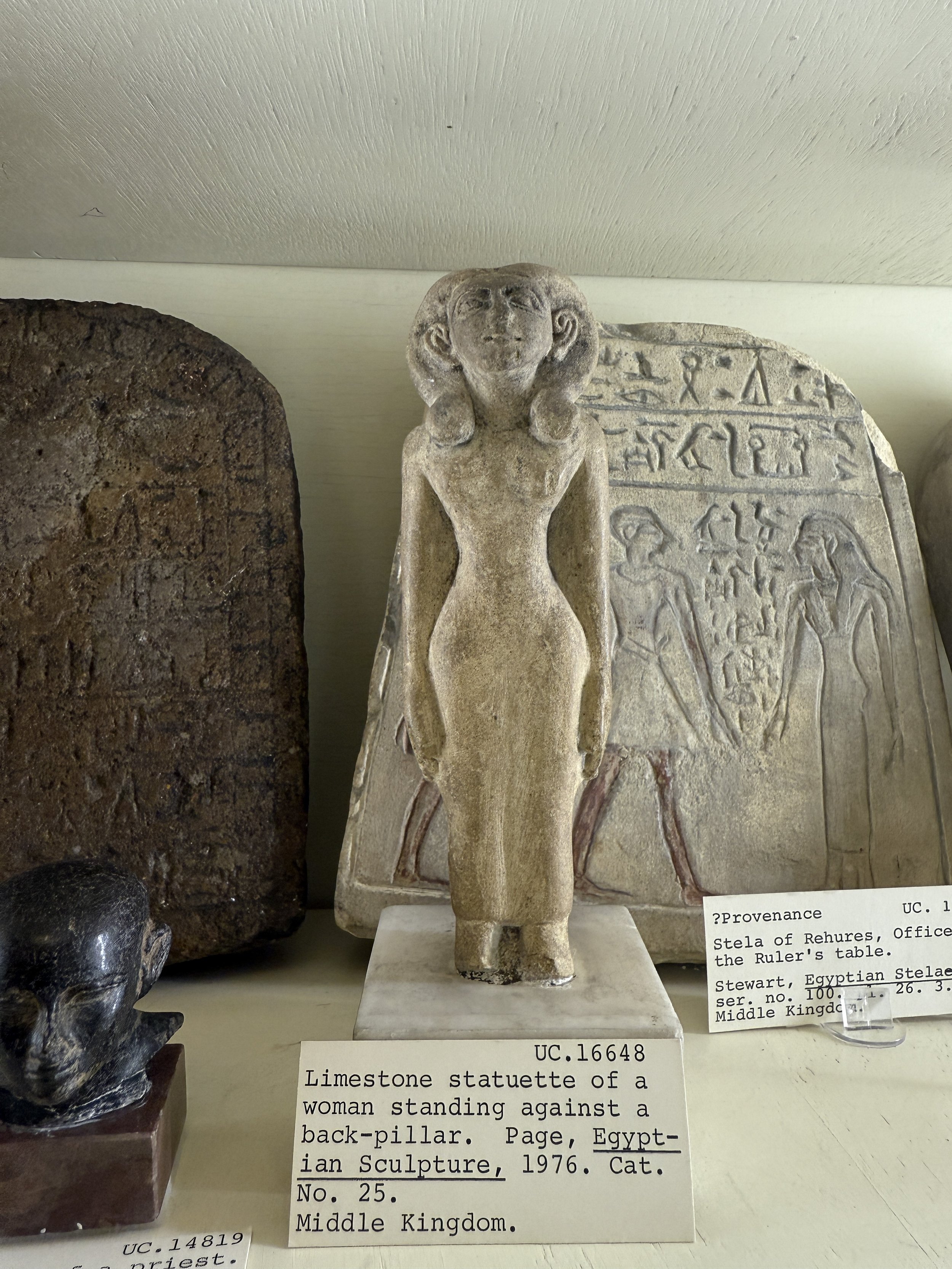

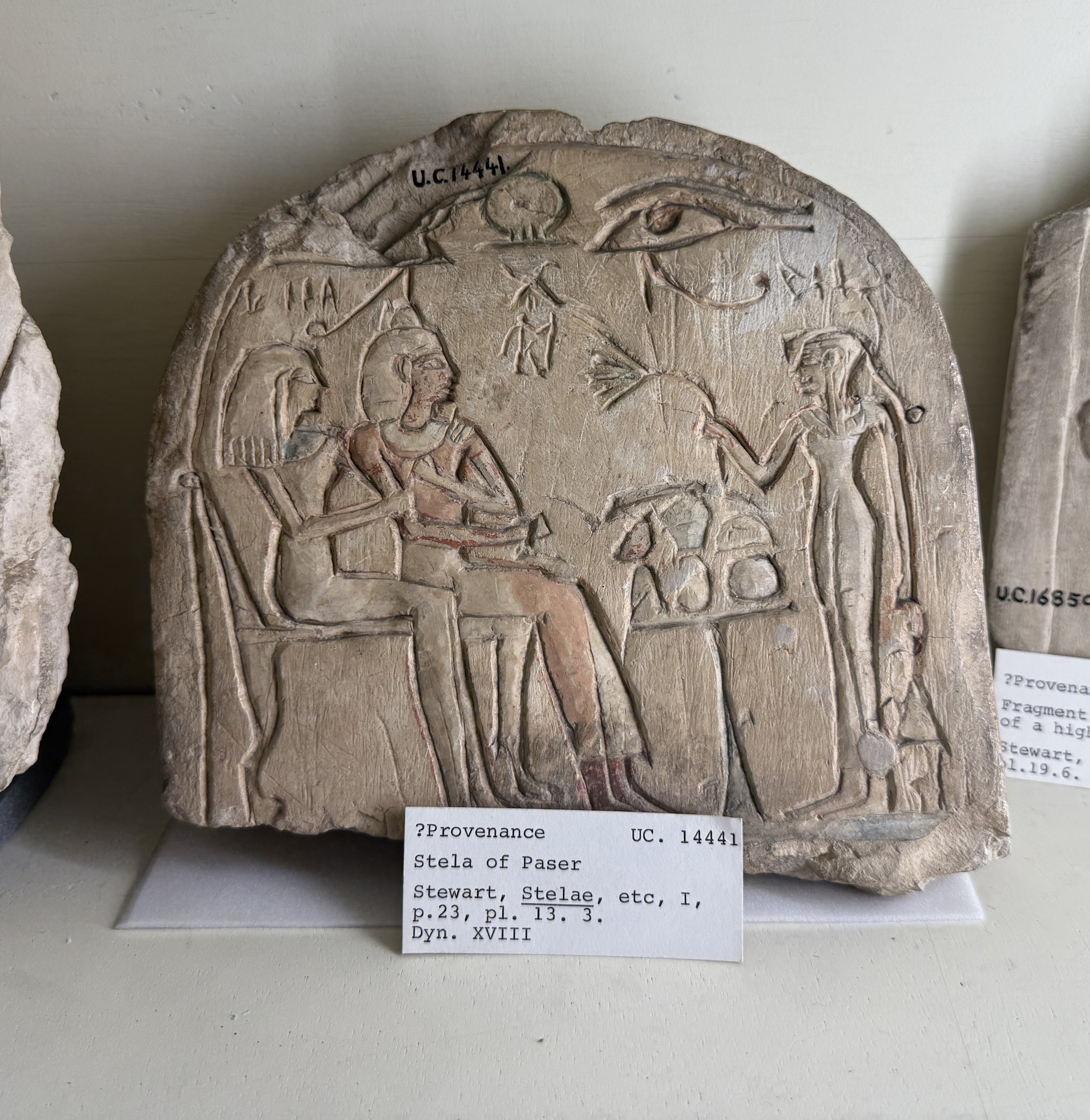

That has to explain why it was such a surprise to discover it—by accident, no less—while looking for another museum around the corner, also part of University College London. The collection includes more than 80,000 objects. We did as much as we could in two phases, before and after lunch, and the boatload of photos below, will, I hope, give you an idea of what’s there.

Amelia Edwards, whose bust and book appear in the photo gallery, was an important source for me. The museum notes, as I realized while writing my book, that her attitude and prejudices reflect her time. This is bound to happen with research. So the trick is to aim for authenticity with hints here and there of the attitudes—because they offer important insights into the times—but to keep the not-so-pleasant stuff subdued. At the same time, I do try not to sound too 21st century, because I don’t want to jar readers out of the world I’ve created. Still, all writers reflect their times. That’s as true of me as it is of Amelia Edwards or any of the numerous other authors whose work I consulted.

As to the artifacts: The museum doesn’t have an elaborate guidebook, so the information is limited to what we (meaning my husband, under my command) could photograph, and I am not an Egyptologist, so I can’t offer further enlightenment. I can tell you one thing: Generally speaking, it’s believed that the shabtis—those little figurines—were meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

Again, you will find very brief videos on my Facebook and Instagram Author pages.